Dr Razan Khogali Othman on the war in Sudan and the challenges to deliver health care services to women

Dr Razan Khogali Othman is a recent medical school graduate from the National Ribat University in Sudan. Throughout her time in university, she focused on the sexual and reproductive health and rights of women and worked with global feminist organisations to address issues such as gender based violence and maternal health. She shares her experiences volunteering at Wad Madani Hospital for Obstetrics and Gynaecology in the context of the war that started in April 2023, highlighting the health needs of women and pressures faced by health care workers in this crisis.

War and its consequences on the health systems in Sudan

The war in Khartoum between the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) militia and Sudanese Army Forces (SAF) that started on the 15 April 2023 forced millions of civilians to flee their homes. Since then, Wad Madani, capital of Aljazeera state, situated 180km away from Khartoum, has been hosting a large portion of those internally displaced by the war, myself included.

Civilians were forced to flee their homes due to the heavy gunfire, the RSF and gangs terrorising the population and looting homes, and the scarcity and inaccessibility of water, electricity and other basic necessities. In addition, the lack of health services, as most hospitals and pharmacies in Khartoum went out of service and collapsed shortly after the war erupted, had a heavy impact on civilians, especially those with chronic illnesses and pregnant women. As a result, cities such as Wad Madani became overwhelmed with internally displaced people, especially those seeking health care.

The conflict has had dire implications for women’s sexual and reproductive health and rights, and many reports of sexual violence committed by the RSF have surfaced. Furthermore, access to maternal health services for women has been a challenge. This is caused by the shutdown of hospitals in Khartoum, difficulties in finding transportation to distant hospitals for those in rural areas due to unsafe roads, and the reduction in the quality of services at hospitals due to the shortage of medical supplies and drugs.

Challenges for women’s health care services in Wad Madani

I started volunteering at Wad Madani Hospital for Obstetrics and Gynaecology a little over three months ago, to support the staff with the huge number of patients they are looking after, and to get a better understanding of the state of sexual reproductive health during this crisis.

Our hospital is currently the biggest centre for obstetrics and gynaecology in the State, receiving thousands of women who escaped the war in Khartoum, those from the smaller cities and villages in Aljazeera state and, of course, the original residents of Wad Madani. For an already under-equipped, understaffed and underfunded hospital, this is an overwhelming amount of patients to manage.

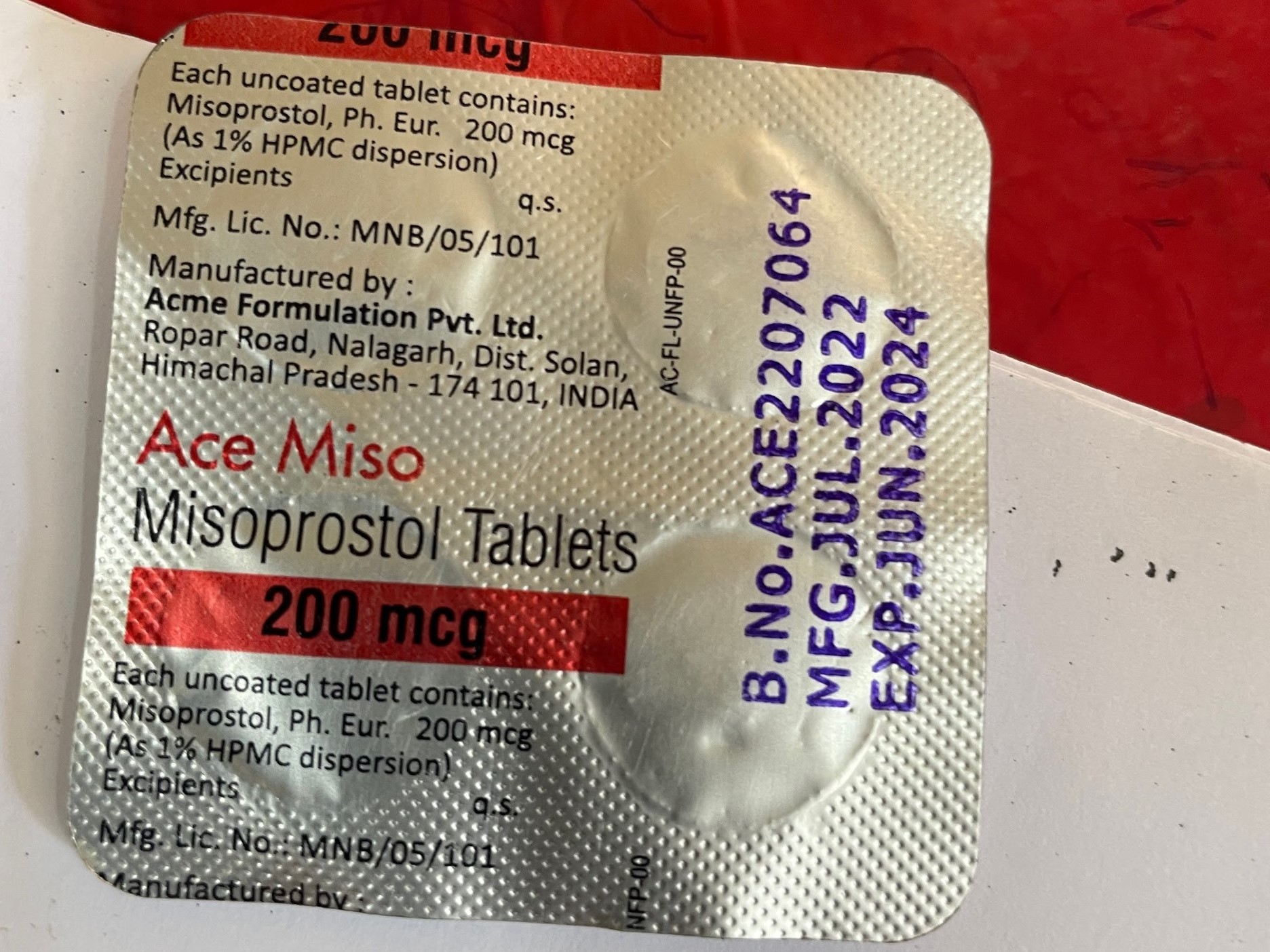

The disruptions to the supply of vital drugs such as misoprostol and oxytocin is imposing a burden on doctors and midwives and challenging the delivery of timely and quality treatments for their patients. While the hospital used to provide these drugs to patients and had a sufficient stock, two months into the war the resources dried out and the hospital started asking patients to bring their own drugs from external pharmacies. For many patients, these drugs can be very hard to obtain, and often an additional cost they cannot afford.

For us as health care providers, there is a real concern surrounding quality control of these drugs. We know that some of them are stored incorrectly due to poor regulation caused by the war, and inadequate medication is still being sold to patients. This reduction in the quality and quantity of drugs can be very dangerous, especially when dealing with emergencies such as postpartum haemorrhage where oxytocin is crucial, or with abortions where misoprostol is needed. In Wad Madani and across all of Sudan, blood supplies are also lacking and excessively expensive.

To illustrate this, I recall a patient with whom we had to use four ampoules of oxytocin (40IU) instead of the usual two during a caesarean section, and these still did not work. The effectiveness of the drug had been compromised due to suboptimal storage, leaving the uterus lax. Due to the unreliability of the drugs we can access, doctors sometimes perform preventive B-lynch procedures during caesarean sections for high-risk patients to prevent complications such as postpartum haemorrhage.

Moving forward for women and the people of Sudan

Doctors are working in an extremely tiring and challenging environment, working long hours, seven days a week in hospitals overcrowded with patients in a setting where vital drugs and supplies are lacking and necessities as basic as water to perform surgical hand scrubbing can stop working at any minute. Yet, doctors are persevering to deliver healthy babies and to keep maternal deaths low.

With each day of this war that passes, the threat to the already fragile and vulnerable health care system in every state of Sudan becomes more alarming. We as Sudanese citizens and as doctors hope that the negotiations and initiatives in Jeddah to stop the war will succeed. However, even if they do, the system has already suffered immensely and it will be a challenge to mitigate the impacts of this war.